A Yakuza Without Honour Isn't Worth Shit

Graveyard(s) of Honor, Yakuza Wildmen, and the Suffering of Women

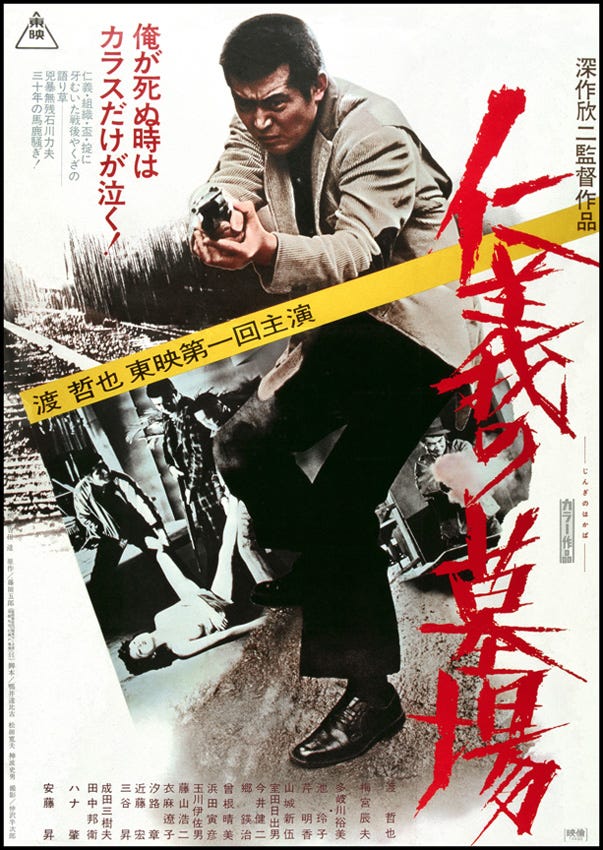

In Kinji Fukasaku’s 1975 film Graveyard of Honor, Tokyo is in tatters. It’s set not long after Japan’s unconditional surrender. Men kill over a bowl of rice, fight off gangs made up of Chinese and Korean nationals, and barter with crooked occupying forces from America. Everyone looks hungry, but no one moreso than Rikio Ishikawa (Tetsuya Watari), imposingly singular and nearly always shielded by dark sunglasses. The young man is cutting a path through the neighborhood as a yakuza enforcer, and offending nearly everyone en route. This terrifyingly callous gangster - purportedly based on a real man of the same name - is a blight on everyone and everything he touches. His respect for authority - a key trait in the structure of the yakuza - is practically nonexistent. Graveyard of Honor would be remade by Takashi Miike in 2002, updating its setting to the late 1980s and early 90s, and the one thing the films have in common is that their protagonist is, fundamentally, terrible.

Fukasaku is probably best-known by English language audiences for his internationally-lauded - and final - film, Battle Royale (2000). But the good and great of his career came long before this. In the seventies, his Hiroshima-set gangland epic, Battles Without Honor or Humanity, takes that distinction. Fukasaku was fifteen when the war ended. He had survived a munitions factory bombing by hiding under the corpses of his classmates. He came of age while, presumably, the real Rikio Ishikawa was prowling Tokyo’s Shinjuku district. With food shortages and death everywhere, it’s not hard to imagine how the young filmmaker’s worldview was shaped: everyone seemed to be out for themselves. This was a time when petty street violence and turf wars broke out constantly; in other words, it was the same world as Ishikawa’s. Fukasaku’s vision of these mobsters, who filched their fortunes like vultures from the steaming wreck of post-war Japan, is understandably jaundiced. Graveyard of Honor would cement Fukasaku’s pivotal part in the rise of the jitsuroku subgenre: Japanese gangster films that depicted real-life and unsympathetic yakuza.

‘Unsympathetic’ is, for most audience members accustomed to crime cinema, not really a problem. But let it be said: our protagonist here is almost unparalleled in his malice. In the opening to the film - peppered with black & white photographs from the real Ishikawa’s childhood - someone opines, ‘It wasn’t the war. He was just crazy’. Crazy, maybe, but also: a serial rapist, a betrayer of friends, a man who responds better to wickedness than to kindness, and treats the former with worse contempt.

Ishikawa finds work as an enforcer for the Kawada clan. It seems to be less a case of a job that requires a sledgehammer than it is a sledgehammer requiring a job. Subject and form are perfectly married through the director’s characteristic and - in this time and place - highly innovative style. His realism is distinctive, but it’s the chaos of his hyperactive, flighty camera that’s dazzling. It swaggers, swerves, and crashes its way through busy Tokyo streets, collapsing to the ground in an extreme Dutch tilt and circling manically around a phalanx of knife-wielding thugs. His work left an enormous imprint on filmmakers like William Friedkin and John Woo.

Ishikawa gets an entire rival gang in hand through sheer brute force. A stint in prison and a burgeoning heroin addiction only magnify his unpredictable rage (an alternative name for the film translated to ‘Psycho Junkie’, a decidedly less dignified title). When Ichikawa tries to assassinate his yakuza boss over a perceived slight, the whole of the Tokyo criminal underworld is set upon him. The cops, too.

But have you noticed yet? I’ve got this far and I haven’t mentioned a woman once. Before you fire me, let me say: this is a pretty fair approximation of where the female characters of Graveyard(s) of Honor rate in terms of their importance. Chieko, played respectively by Yumi Takigawa in the 1975 version and in a much expanded role in Miike’s film by Narimi Arimori, is the most prominent of the many women victimised by yakuza men.

In the ‘75 version, she is a sex worker — Shinjuku was a hotspot for sex work immediately after the war and is still considered a red light district today. Her room becomes first a source of unintentional safety for Ichikawa as he runs from his gun-toting enemies; but then it becomes a place of danger for her. He not only rapes her, but continues to visit her at the brothel as though they have formed some perverse romance through their encounter. The fact was that many Shinjuku brothels were actually staffed by the Japanese government, who recruited sex workers through the ‘Recreation and Amusement Association’ and aimed their wares at American GIs for a darkly pragmatic purpose: to keep them from raping civilian Japanese women. That Ichikawa has so little decency that he is hardly different from an enemy occupier seems pretty pointed, on Fukasaku’s part. But then: Chieko remains, for mysterious reasons, attached to Ichikawa, loaning him money for bail and forming a sickeningly codependent relationship with him — right up until her death. If you think this all sounds bad enough as it is, throw in a mutual heroin habit and a boyfriend who best chooses to memorialise you by chewing on your half-cremated bones.

Ichikawa may be an extreme case, but the relationship between women and the yakuza is - inasmuch as anyone has been able to get close enough to find out and report back in English - pretty tough to navigate. Like most other forms of historical organised crime across the world, the yakuza is dominated by men. Women are technically not allowed to join the ranks or be a part of the clan hierarchy. The yakuza is a brotherhood, led by ‘fathers’, and its traditional structure requires its women to be pliant and supportive. There are always exceptions that prove the rule - like the yakuza-associated women who have gang-related tattoos. But as the above piece informs us:

In her thesis, criminology academic Rie Alkemade, points out: ‘Unlike Western mafia wives, Yakuza wives remain outside the sphere of criminal activity in this organised crime structure, remaining in the passive emotionally and financially supportive role.’

In Fukasaku’s film, Chieko’s tragic story is only one part of the incredible trail of damage that Ichikawa leaves in his wake. But if Fukasaku is systematically deglamourising the idea of an ‘honourable’ yakuza, Takashi Miike’s remake is exploding it entirely. And it is Chieko who offers the sternest possible rebuke to those of us in thrall to the excitement of the Japanese criminal underworld.

In a 2017 interview with MUBI, Takashi Miike said he hardly ever rewatches his old films. But on the odd occasion that he does, he usually finds them too violent.

Frankly, I can sympathise. The grotesquerie of films like Ichi the Killer (2001) and Audition (1999), with all their nipple removals and syringes to the eyeball seem to pale in comparison to the different kinds of violence on display in his Graveyard of Honor (2002). In the first twenty minutes of its opening, its lead - renamed Rikuo Ishimatsu (Gorô Kishitani) rapes a waitress, and then he will go home and rape his own wife, Chieko (Narimi Arimori).

When Ishamatsu first bursts through the door, she cowers from him in a corner. Suffice it to say, there is nothing about this Graveyard of Honor that’s easy to watch. Neither version pulls its punches about anything its protagonist does, up to and including sexual violence, but in Miike’s version, we see it multiple times, abruptly and brutally. In today’s landscape especially, there’s a good chance audiences might struggle to watch it at all. The seep of real evil is so apparent in Miike’s film that it seems to leave a stain on the mind. Not only is Chieko beaten by Ishamatsu, she’s beaten in her own home by a yakuza gang who are out hunting for her husband; she is sucked into the undertow of an addiction which, in this version, explicitly kills her. She doesn’t leave him throughout any of it.

In some respects, Gorô Kishitani gives a more vicious performance than Tetsuya Watari, who in the original film seems almost circumspect by comparison. Watari is all swagger, dark sunglasses indoors, self-destructive energy; his evil is evidenced by his deeds more than his demeanour. Not so for Kishitani, who amps up the devilish glee in his eye as he kicks and hacks enemies to death. His face is almost geometrically structured for malice, his empty stare daring you to recoil. His indifference is almost worse than hostility. Every moment of choreographed brutality is, honestly made scarier because of his malevolence. (It’s hard to think of a character whose comeuppance I’ve wished for more.)

Miike’s version is arguably harder to watch than Fukasaku’s. Most agree that the original film is better, and I’d be inclined to say so myself: its postwar setting makes sense, and there are some anachronisms borne out of updating it to a contemporary period. Fukusaku is difficult to match in the artful chaos of his whirling style; Miike doesn’t really make the mistake of trying. His style is more wilfully restrained, his pacing slower - even languorous - and his tone almost funereal, lacking the odd pop of cheeky humour Miike is known for. It’s a choice that makes what is an instant of violence and a splash of crimson in Fukasaku’s version feel like it lasts a lifetime in Miike’s; this is slow sadism, never rushing the viewer through its worst moments.

‘I like traditional yakuza films. I generally prefer the orthodox to the innovative,’ Miike told the co-authors of Agitator: The Cinema of Takashi Miike, a 2003 book about his work. Maybe that’s why it scans that Miike is pretty loyal to Fukasaku’s conclusion: this is a self-made monster who will self-destruct, and does so spectacularly, by throwing himself clean off a prison wall and hitting the pavement with a sickening splash of viscera. It’s hard to feel even a little bit bad about his end, given the entire runtime of the film prior.

You might wonder, given the subject of this newsletter, why I would want to write about these films. I would struggle to call either iteration of Graveyard of Honor 'feminist', and they certainly do not treat their female characters well in any traditional sense. But there Miike's film has a willingness to take Fukasaku's very real disgust with yakuza thugs like this to its furthest logical extension. In this endurance-testing horrorshow of a gangland saga, he offers us an unpleasant truth. He asks his fellow genre fans to examine territory that - as a director who has made a great number of yakuza films - nearly tears down the entire edifice. In Ishamatsu, he finds a man who seeks to maim everything he touches, who turns on his 'brothers' in fits of megalomaniacal paranoia, who has no regard for anything but his own gratification, whose pointless sadism is garish and terrifying.

Fittingly, I suppose, is the equal and opposite reality. Alongside him is no movie archetype: not the conniving femme fatale, not the secret power-broker, not a tidy well of internal and long-suffering strength we could look to for female empowerment. Instead, there is a terrified, brutalised woman who, like many victims of domestic and sexual abuse, is unable to find her way out of her situation.

Graveyard of Honor isn’t telling us to break off our love affair with yakuza, as such. But it is asking us what anyone in their right mind would ask Chieko. Is he worth it?

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Thank you for reading Sisters Under the Mink. If you like it, please feel free to share it on socials, subscribe, or upgrade your subscription below!

A fascinating read. I might give the Fukasaku version a go, but Miike even more off the leash than usual might be a bit much!

My sense is that the Yakuza are even more mythologised than their American counterparts, I'm not sure we've really got past the trope of the western cop being led around by the Japan Expert who repeatedly explains how honour is really a very important concept before someone cuts their finger off with a katana? And thinking about it, the depiction of women doesn't often go beyond some Japanese stereotypes. Definitely a setting that needs new stories?