Dudes (do not) Rock: Au revoir, Monsieur Delon

On the Passing of A Beautiful Monster, Alain Delon

Hi, welcome back to Sisters Under the Mink’s ongoing essay series, Dudes Rock!, about men and masculinity at the movies. I felt I absolutely had to write about the loss of the great film star Alain Delon, and his legacy. Please forgive my lateness, but expect plenty more to come from me this month!

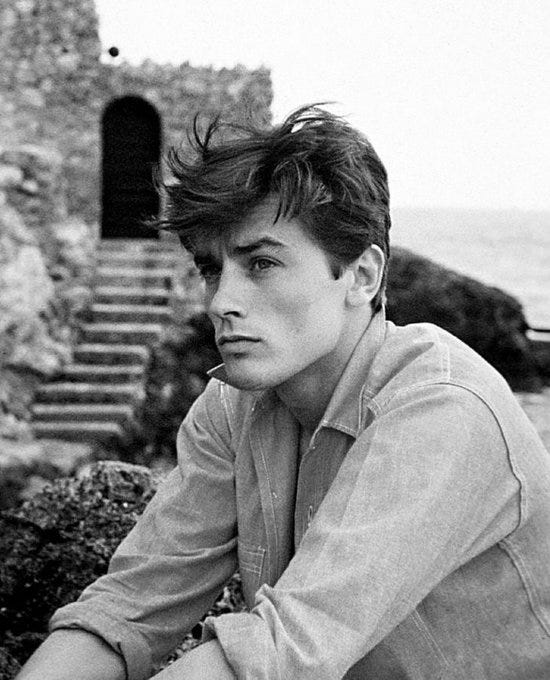

If you care about movies, you probably heard about the passing of French superstar Alain Delon a few weeks ago, aged 88. If you didn’t know anything about him & wanted to boil it down to two main takeaways from the various obits and tributes: he was beautiful, and he was terrible. Here was an icon of 60s cinema and a total bully; a tough-guy actor with an angelic face, who spent much of his time hanging out with gangster thugs and right-wing politicians. For someone whose bread & butter has long been classic cinema, the conundrum of great movies made by bad people is hardly new to me. I have long loved and admired film stars and artists who give you cause to do a lot of so-called ‘separating’ from the art. But let’s hold that thought for a moment, here, and talk about the art.

I saw images of Alain Delon before I ever saw one of his films. Firstly: his deceptive boyishness and cold stare under a fedora in Le Samourai (1967), and him looking tanned and seductive in Plein Soleil (1960), Rene Clement’s French adaptation of Patricia Highsmith’s The Talented Mr. Ripley. I have loved him since I was a teenager with a Tumblr, following a lot of 60s French cinema accounts because of my fondness for Jean-Luc Godard. One day, I was scrolling aimlessly and nearly struck down dead by the concentrated erotic power of a gif of Delon as the aforementioned Ripley. I had to know who this man was, and how it was possible for someone to look like that.

It feels a touch silly to mention this before discussing Delon’s towering place in Melville’s ritualistic crime cinema (Le Cercle Rouge is a favourite) or Luchino Visconti’s sweeping images of decadence and decay (The Leopard, Rocco and his Brothers). But the fact remains that no matter how you first encounter him, Alain Delon -- above and beyond looking like that -- is startling. It’s the word I keep thinking of when I try to articulate what it is that’s so special about him as an actor. Yes, he startled me that day while I was scrolling Tumblr. But it’s much more than that: it’s in his body language, his physicality itself. Here is an actor who is so still, so controlled; precise in both his movement and his mien. He has a watchful, silent quality, coiled as though he’s about to strike. And he often is.

So purposeful is he that whenever he opens his mouth and speaks, or jerks a gun out of his pocket, it has the same impact as when a sleek grey-eyed cat silently and abruptly lands in front of you: it makes you want to jump. He is unnerving. His performances are often about the economy of gesture, of movement. He is a perfect foil to, say, a Cagney or a Brando, who are all about excess of gesture. He matched the logic of Jean-Pierre Melville’s work perfectly because both understood a thing or two about restraint and minimalism.

Delon once said to an interviewer that one of the actors he most admired was also an all-time favourite of mine: Montgomery Clift, who, as an early proponent of the Method, was spellbinding in films like A Place in the Sun (1951) and From Here to Eternity (1953). The reason, he said, was that Clift ‘never moved a muscle unnecessarily’; it’s a trait Delon shares beautifully. Required to play the role of a possibly-manipulative suitor to a wealthy shut-in in The Heiress (1949), Clift never tips his hand and reveals his true motivation, but something in his immaculate profile betrays a twitchiness; you could imagine Delon taking on a remake, embodying the same amoral charm.

And it’s not that you should read morals into physiognomy, but all stardom contains an element of this, and Delon’s brooding, pretty features -- specifically in his youth -- give him a too-good-to-be-true quality that begs him to misbehave or knock the halo off. This was certainly the case in real life; Delon was kicked out of school multiple times, joined the army and went to Indochina, only to be discharged for stealing a jeep. He hung around with the demi-monde of prizefighters and ne’er-do-wells of Paris as a young actor. Over his many decades of fame, Delon repeatedly shrugged off his friendship with the French far right; denied the paternity of and abandoned one of his children; and that’s before you get to the murder trial. In 1968, when the actor was at the height of his international mega-stardom, he was questioned for involvement in the homicide of his friend and (rumoured) bodyguard Stefan Marković.

In La Piscine (1969), another of his best-known and loved films by audiences today, Delon plays a murderer, too. The vibe is closer to the real-life Delon mythos of perma-tanned, glamorous French Riviera sensuality. That film is a continuation of sorts of the Plein Soleil vein -- in both films, Delon plays men consumed by lust and envy, capable of Machiavellian feats of evil hidden behind angelic charm. It was during the making of La Piscine that the body of Marković was found in a dumpster in Paris.

The Marković affair was a complicated and seedy political scandal with far-reaching implications, but the gist is this: Marković had a habit of collecting blackmail - ie compromising sexual photographs - of influential and powerful people, and one of those people was future President Georges Pompidou’s wife. Suddenly, Marković wound up dead, and Delon’s close friend - a Corsican gangster named Francois Marcantoni - was initially charged for that murder. Delon and his estranged wife Nathalie were questioned extensively, but nothing ultimately came of it. To complicate matters further, Nathalie had apparently been Markovic’s mistress at one point.

In interviews, Delon remained untroubled by his association to criminality, saying, ‘It’s a question of origin. I myself am Corsican, and in places like that they still have a sense of honour and the given word. [...]I don't worry about what a friend does. Each one is responsible for his own act. It doesn't matter what he does. Most of the gangsters I know... were my friends before I became an actor.’ The case remains unsolved today.

To add insult to injury, news in the days after Delon’s death unveiled his desire to have his beloved Malinois dog apparently euthanised to join him in the grave because the dog would “miss him too much”. Redolent of the arrogance of an Egyptian pharaoh wanting to be entombed with his treasures, the headlines came as a kind of additional smack of recognition that: no, this was not a man inclined to think of others first. I can’t say I was surprised, but it was just one more reminder of a rather staggering pile of evidence to suggest this was not a nice man.

You might say that Delon could personify screen gangsters and Very Bad Men because his good looks were mitigated by veins full of ice water. If you wanted to read biography directly onto art, you could even argue that Delon’s own egotism and possible cruelty informed his talent at playing men like these; he certainly associated with them. But that undermines his actual talent and versatility as an actor, beyond the trench coat-donning solitary hitman of Jef Costello in Le Samourai or the nattily-attired, lighthearted rogue of Jacques Deray’s Borsalino. Delon proves his flexibility and skill beyond typecasting throughout his work, from the heroic sweetness of his protagonist in Rocco and his Brothers, right on through to his later work, from Godard’s Nouvelle Vague (1990) to Joseph Losey’s Mr. Klein (1976), a remarkable film about the moral reckoning of a Vichy art dealer who opportunistically trades in stolen goods from persecuted Jews during the war.

Ultimately I wonder what it means, right down at the heart of it, for an actor to pal around with people like Le Pen - basically fascists - and possible murderers, and to also be capable of such transcendent performances in films of profound sensitivity. Some might argue this is more down to directorial talent than any governing moral intelligence on the part of an actor. But if Delon was merely an unfeeling swine, could he so aptly display the emotional dexterity he did in his career? In both the moral apathy and dawning horror of Mr. Klein, or the Christ-like, self-annihilating loyalty of young Rocco, he reveals self-awareness and nuance. I do not see Delon as a puppet or a passive figure in his career, and he clearly did not, either. In a 1970 broadcast with talk show host Dick Cavett, Delon said of his brush with scandal that he had made a television appeal to the French public, and that they still loved him. ‘When you have the audience on your side, you just can’t lose,’ he said. For better or worse, he seems to have been proven right.

The great Joseph Losey, who directed Delon in Mr. Klein, said of the actor that ‘every aspect of his life reflects great and often contradictory complexity,’ and perhaps that brings me to think: loving great cinema and caring about the art of ignoble men is to search constantly for that complexity, for scraps of their goodness, glimmers of redemption - even unintentional ones - within their work. It’s hard not to feel that way about Delon, who has so clearly been a bad man as well as playing one, and who - go figure - I’m sad is no longer in the world with us, nonetheless.

~~~~

Thank you for reading Sisters Under the Mink and checking out this essay series. If you’d like to continue reading, you can upgrade to a paid sub below!