Dudes Rock!, or: The Reformed Jock of Modern Cinema

On Challengers, The Iron Claw, and Sensitive Athletes

Hi, and welcome to Dudes Rock! - an essay series exploring the depiction of bros at the movies in all their various guises. Today: I’m thinking about the long tradition of the screen jock, and whether he’s become reformed for the modern audience: the athletes of Everybody Wants Some!!!, The Iron Claw, and Challengers and how they differ from their predecessors. This is the last free essay in the series, which will continue throughout the summer, with further discussion on the iconography of men and masculinity at the movies. You can upgrade to a paid sub to read the rest of Dudes Rock!

I don’t think you have to be American to appreciate the all-encompassing symbolism of the jock, though he is often most at home there, where cinema and sports culture and Americana have deified him beyond all belief. Movies from Bull Durham to Animal House and beyond have sentimentalised the lives and also glorified the Alpha Male silliness of athletes. So much so that even those of us who should know better might be seduced by the square-jawed minor heroics of a varsity touchdown in a Hollywood movie. They’re the ‘male weepies’ of Rocky and Rudy, or the fun & games of Varsity Blues (1999), or a gridiron drama like The Longest Yard (1974).

And yet, with a laundry list of scandals around #MeToo and college sports coaches, and the excerable behaviour of frat boys since time immemorial, there’s a little bit of shine rubbed off the corners of this once-golden image of American manhood. So it’s fascinating to me that in an era where everyone is obsessed with the concept of toxic masculinity, in the past few years there have been a trickle of films where the jock is portrayed in a far more sensitive light; he can cry without fear, show tenderness for his buddies, maybe even acknowledge the homoeroticism of the locker room. Some of those films are period pieces, which is revealing – there’s a sense that placing a jock’s story in the past allows the filmmaker to comment better on old-timey attitudes; and for the audience to feel more at ease with the old-school macho environment, while also maybe softening the recent past.

Perhaps it’s a fantasy to reform the screen jock, after all this time he’s spent knocking our books out of our hands in the hallway. But what a fantasy to behold, right? He’s the reimagined Adonis, the anti-Robert Redford in Downhill Racer (one of the great, early ‘you do not have to be nice to be good at sports’ movies) or, more realistically, the red-nosed rugby bully at your school. He’s Glen Powell kindly picking those books up, or Zac Efron, looking ‘roided up to the eyeballs but needing a giant hug. It’s not the old bad rough-and-tough sweaty macho guy our dads were rooting for, like Burt Reynolds (a football hero in Semi-Tough and The Longest Yard), OJ Simpson, (a real football hero turned comedy star, and I imagine you know the rest), or other pituitary cases. But it is still of a piece with that, because isn’t it the dream of hetero-masculinity that we still get to have a little taste of this red-bloodedness, without all the stuff we’re not meant to like about it?

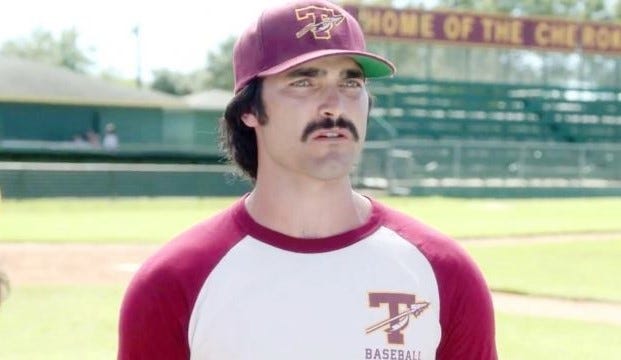

There’s a bit of this contradiction in Richard Linklater’s jovial jock hangout flick from 2016, Everybody Wants Some!!!. It’s the filmmaker’s own semi-autobiographical story of being a freshman college baseball player in 1980 Texas. No story about one’s own experience is likely to be without some nostalgia, but the specificity of the film’s time and place also helps it in another way. The often amusing retro stylings that come with the film – the popularity of both disco and honky-tonk music, the exceptional series of short shorts and tight tank-tops on display, the variety of moustaches -- gives the viewer some distance from the modern reality of the frat house. These guys swear and drink and obsess over getting women, but they aren’t racist or sexist. It softens the obnoxiousness of the bro characters, who are often as young, dumb, and full of come as you’d expect. The lead, played by Blake Jenner, is wide-eyed but also almost ridiculously self-assured for a new-on-the-scene freshman – he quickly gains respect and friendship in part because of his swagger. Among the gang is the preternaturally talented and annoyingly handsome McReynolds (Tyler Hoechlin) and the motor-mouthed, cod-philosophising Finnegan, played by Glen Powell in a part which he, if you have any familiarity with him IRL, had clearly been improvising dialogue for. (That man is a dorky theatre kid at heart.) It all feels like a bit of a fairy tale of nice-guy athleticism, but Linklater does, at least, have the good graces to make these guys stupid.

Ultimately, the boys’ constant one-upmanship and testosterone-driven competitiveness is more funnily recognisable than it is a punishing examination of masculinity. Newsflash: college-age guys are dumb and get angry over stuff like table tennis games. Their entire mode of bonding is about insulting each other or playing games of some kind; it’s pretty harmless. Linklater’s film is unusual for its relatively uncomplicated (and crucially, very funny) depiction of guys being dudes. There’s something wholesome about how silly it all is; on a recent rewatch, I found myself affectionately eye-rolling at their antics, which feels like the sweet spot for a female viewer, ultimately. Everybody Wants Some!! is about male friendship, and being young and unformed, and really only being good at one thing (sports) to the detriment of nearly everything else. It’s nostalgic about the brief period of innocence when nothing else has to matter that much, and that’s a lovely thing.

Another film which takes great pleasure and care in depicting wholesome, fun-loving bro hangouts (with literal brothers, in this case) is Sean Durkin’s wrestling melodrama The Iron Claw (2023). It is also, funnily enough, set in 1980s Texas, and Durkin makes great use of the period as Linklater does, depicting carefree perma-tanned teens with their cropped denim and bombastic radio rock. The film is a three-hankie weepie, loosely fictionalising the tragic true story of the Von Erich wrestling dynasty. The dad, Fritz, a former wrestler himself (played with phenomenal skill by Holt McCallany) is a hard-driving coach to his four sons, determined that one of them will win the WWE heavyweight championship but pushing them to intense emotional and physical limits.

The film opens with a curious close-up of a sleeping Kevin Von Erich (Zac Efron), still sharing a teen bedroom with his brother (Harris Dickinson). That close-up is an off-kilter shot of his bicep, so large and fake-tanned per the wrestling aesthetic of the time that it obscures the view of the rest of him. It feels pointed that it’s how we first meet Kevin. Often, though not always, athleticism onscreen manifests as hulking shoulders and bulging corpuscles (in the 80s, particularly so). But never has a film so aggressively turned the Reagan-era dream of musclebound power into one of powerlessness and tragedy.

Zac Efron, with anguished eyes and a giant, near-ridiculous frame, is remarkable as Kevin. His voiceover provides a kind of heartbreaking coda to the story of his family’s personal tragedy, and the hard-driving ambition of their father, which eventually, in part, pushes them to ruin. ‘Pop tried to protect us with wrestling. He said if we were the toughest, the strongest, the most successful, nothing can ever hurt us. I believed him; we all did.’

It’s this search for a form of immortality - and a long-held belief that adversity only aids the would-be sports champion - that has wreaked such havoc. The heartbreaking finale of The Iron Claw, in which male tenderness, tears, and love overcome physical prowess or sports ambition has much to say about the devastating impact that patriarchal ego can have.

Ambition is also wielded like a cudgel in Challengers, although it is located in a very different milieu, and tellingly, with a female character, Tashi Duncan (Zendaya.) Her stymied athletic drive is the centrifugal force of the film, and her love of competition – on and off the court – spurs everything else into motion. She’s a future tennis superstar, until an ACL injury ruins her plans; she turns to being a trainer-wife instead. What fascinates me about the jocks of Luca Guadagnino’s menage-a-trois sports romp (besides the fact there’s not enough fucking in it) is how it softens the image of the macho jock not by making him nicer or more glamourous, but by making him a tiny bit ridiculous, and self-important.

Art (Mike Faist) and Patrick (Josh O’Connor) are best friends and tennis up-and-comers who went to private tennis academy together, and were bunkmates at boarding school from the age of twelve. The homoerotic frisson between them is self-evident, with Tashi - the object of their shared affections - joking that she isn’t a ‘homewrecker’. These sports bros should maybe be a bit more dignified, given their upper-crust backgrounds and the generally more classy milieu of professional tennis; but they are not remotely sophisticated. When shown in flashback as their younger selves, they spend their time bickering and gawping at Tashi in protracted, absurd fashion. All of this leads to the encounter between the three of them in a hotel room, where Patrick shares a pubescent story of teaching his pal Art how to jerk off – hardly the stuff of macho tennis star dreams.

Again and again, Guadagnino shows the imperfection of these would-be athlete heroes. Art is wheedling and two-faced when he tries to worm his way between Tashi and Patrick; Patrick is arrogant and sleazy, using charm (and ‘a big dick’, as Tashi points out) to paper over the cracks in his personality. Nobody is entirely likeable here, but they have their appeals – not to mention a sparky sexual chemistry.

There is something delicious about seeing O’Connor and Faist so physically close to one another, intimate in a mostly nonsexual way, and so comfortable with it, in a way (ostensibly) straight men rarely seem to be. Art and Patrick hang around in their underwear smoking in a hotel room, with their bare feet in the other’s face. Later, when Patrick playfully calls Art a snake, the pair are practically nose to nose, smiling gently as they spar, rather than taking on an aggressive stance. The thought of competing for Tashi’s attention is both a source of jealousy and of seeming frisson. Guadagnino is not a subtle filmmaker - though he tends to make up for it with oodles of style, all snap zooms and Trent Reznor’s electrifying soundtrack. The tennis analogies are frequently made literal by the characters in speech. (‘You don’t understand tennis. It’s a relationship,’ Tashi advises early in the film, and this bears itself out.)

In similarly unsubtle imagery, Art flirtatiously takes a bite of the churro Patrick is holding when they tease each other over Tashi. Later, Patrick is seen chomping hungrily on a banana courtside in his grudge match against Art. With these borderline-comic phallic symbols, they are metaphorically castrating one another in each scene, but they are also doing it with their mouths, which is undeniably…well….you know. It’s not that toxic masculinity, or whatever you want to call it, isn’t at play in Challengers – far from it, with Art and Patrick’s vicious psychosexual battle for domination and ownership. But Tashi runs the game. She is the expert tennis trainer, the real professional, the one who wants to talk tennis instead of (during) sex. Art Donaldson’s mega-success and Aston Martin sponsorship deals are as much down to her, as his wife-trainer, than they are to his own prowess on the court. Guadagnino thus destabilises the image of the tennis jock — but not so much so that we don’t find them sexy.

To a lesser or greater extent, each of these films asks if we get to have our cake and eat it; if this newer appreciation of the jock is not merely as sex object and as an exemplar of physical talent, but as an ideal of new and sensitive manliness. In the best filmmakers’ hands, he’s become a vehicle to pick apart the strictures, repressions, and damages of old, bad jock culture (The Iron Claw, I think, stands at the top of this pile). But he also provides a touch of winking reassurance for our bad consciences. If we make our jocks palatable, maybe we feel like old-style masculinity can evolve or transform without losing its essence.

And listen: I should know better. I am American, after all, and went to a conservative small-town high school. Those guys were less Zac Efron and more Mark Wahlberg, and they grew up and joined either the marines or the police. But their film counterparts do provide us a stopgap measure. If I were being cynical, I would say that the reformed jock is a way to keep us from more radical or revolutionary ideas about gender, power, and athleticism. After all, even the ones who are still obnoxiously chasing women and puffing out their chests like roosters, a la Everybody Wants Some, are eminently likeable.

But cynicism would also discount the fundamental thing about this crop of films. These guys exist, and will continue to; they’re shaped by a confluence of machismo and male social conditioning which won’t go away particularly soon; and that the glorious, Nike ad image and the screen subversion of it is a rich sandbox for those reasons. If the movie jock is an expression of how we feel about men in an exaggerated form, these films suggest we are both trying to reform him into sensitivity, and desperately want him to score that touchdown.

~~~

Thank you so much for subscribing to/reading Sisters Under the Mink and checking out this new essay series, Dudes Rock! Part Two, on the history & iconography of the screen athlete (ft. himbos a la Burt Reynolds and Robert Redford) will be forthcoming this month, and this overarching essay series will continue through the summer on a bimonthly basis. This will be the last free essay of the series, so if you’d like to read more, you can sub for only £5 per month!

I loooved this. I think athleticism/jock energy is something we’re collectively and tentatively re-negotiating after the world hit the logical extreme of nerd energy (Marvel movies, um actuallying, romanticized introversion, Silicon Valley) in the late 2010s and realized it sucked

As always, nonpareil writing Christina! Downright envious of your ability to seamlessly drill beneath superficial norms and elucidate hyper-specific tropes with ease. And as a baseball fanatic, I'm surprised I haven't checked out "Everybody Wants Some!!." I need to change that.