Dudes Rock! The 70s Jock, North Dallas Forty, and a Crisis of Confidence

On idealism and fatalism in 70s sports flicks

This is part two of Dudes Rock!, an ongoing essay series attempting to understand bros at the movies. This week, an examination of the unreformed jock of the 1970s. This post (and the audio version) is exclusive to paid subscribers.

‘I love your legs. They got your feet on one end and your pussy on the other.’

— Jo Bob (Bo Svenson), North Dallas Forty

The decade of Burt Reynolds as the ur-athlete of his generation. The decade of The Bad News Bears and The Longest Yard. The decade where the bombshell movie star of her time, Raquel Welch, formed a celebrity power couple with mega-star New York Jets quarterback Joe Namath. It was a time of burly he-men and the Wide World of Sports. Famous jocks from George Best to the aforementioned ‘Broadway’ Joe Namath were party boys as well as athletes, with their fair share of codeine, benzedrine, and amyl nitrate to keep them going.

Of course, screen athletes predate the 1970s, and fall into all sorts of categories, but cinema’s sexual and social politics shifted enormously from the Nixon administration onward, and the sports movie served as a fascinating vessel for all the contradictions & difficulties of Being A Man in The World. If recent filmmakers have had a tendency to try and upbraid, revise, and even reform the image of the jock, it’s interesting to take a look at what image older films might have been transmitting in the first place. The rise in popularity of a particular kind of sports film in this period - i.e. of the spit-and-sawdust good times of rollickingly profane jocks and good ole boys - think Slap Shot (1977) - does not seem like an accident. If Rocky (1976) was a metaphor about a white, working-class American man proving there was some fight left in the old dog (pointedly, against a Black opponent), plenty of other sports films of the decade were also working to defeat the malaise of the age.

If you’re thinking about leading men of the 1970s, Robert Redford was also particularly good at walloping back that malaise: he provided jock fantasy, and comfort, rather than realism or roughness, but it worked. The WASP-aloof golden prince played an athlete a handful of times, from his early role as a cruelly ambitious skier in Downhill Racer (1969) to a baseball legend in The Natural (1984 ). But even when he isn’t swinging a racket in pristine tennis whites or adjusting the sails of a New England schooner, this kind of imagery suits the man; his appeal is, fundamentally, the same as an impossible high school quarterback or a Princeton rowing captain. (It’s also, possibly, a statement on the ways in which American movies were briefly inclined toward the pessimistic and the jaded that his film from ‘69 is far harder-edged than his one from ‘84.)

The reason I bring up Redford as a screen jock is because he is so representative of an ‘ideal’ in the old-fashioned sense - refined, not crude, seemingly impervious to sweat or knee injury. Even when he’s not particularly nice, as in Downhill Racer, it’s a kind of masculinity - a kind of life, a kind of America - as cosily aspirational as a Brooks Brothers suit or a house in the Hamptons. And it’s sort of irritating that it’s oddly appealing when mostly this type of thing makes me break out in hives, but my point is that there’s a white-collar, shiny symbolism to certain types of American jock, and it’s none too far away from a Norman Rockwell image.

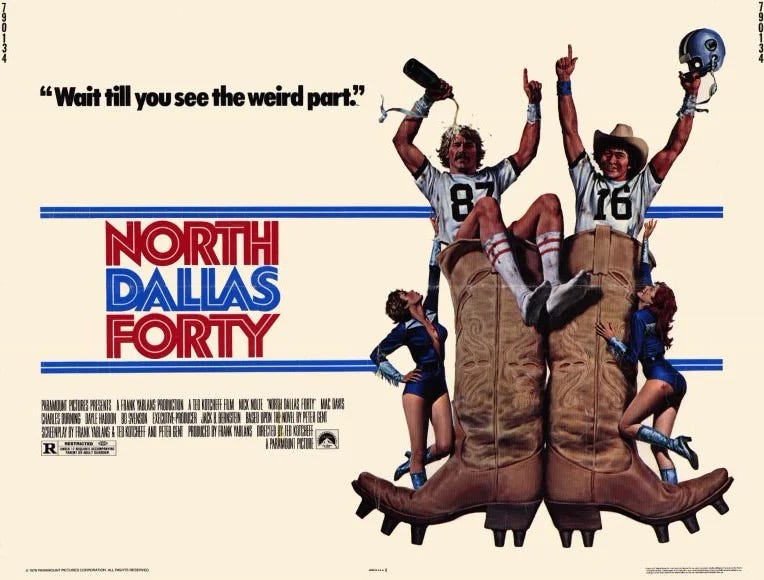

That brings me to Ted Koetcheff’s satire North Dallas Forty (1979), an adaptation of a novel written by Dallas Cowboys wide receiver Peter Gent. It could not possibly work harder against the Redford playbook. That same year, 1979, President Jimmy Carter gave his infamous ‘crisis of confidence’ speech, addressing the shock of loss in Vietnam (America had no framework for losing a war) and the economic downturn that had forced a generation of working-class men onto the backfoot. The sexual revolution had been and gone, allowing women to assert themselves in life and the workplace in a way which only heightened male anxiety; it only stands to reason that the football hero of previous generations had some of their glamour worn off. North Dallas Forty aggressively undermines that glamour.

The protagonist is the beaten-up Phil Elliot, pro football player reaching the end of his tenure - he’s played by a young, normal-looking, moustachioed Nick Nolte, in case anyone forgot he was a good actor. While the film is poised on the cusp of the Reagan era, it most definitely belongs, spiritually, to the 70s – it has not entered the slick corporate sports world that we would later come to associate to that time. Think of the commercial sheen of professional football as depicted by films like Jerry Maguire or Any Given Sunday, and compare them to whatever in the name of fuck is going on in North Dallas Forty – a grimy, sweaty, and sometimes intentionally repulsive film. Nolte’s Phil Elliot is shown, from the start, as the walking wounded: his knee bears surgery scars, his shoulder is in agony, and he labours for breath as he dumps his carcass into a bathtub. He also drinks, smokes, and pops painkillers with abandon; he is not at all unusual amongst his teammates, who almost without exception also look tired, hurt, and over forty. (Digression: is this just a seventies thing? So many young actors had deep creases on their faces and weird hairlines and then you google the actor and realise they were 30 years old at the time.)

And then, there’s the Redford jab. A minor character in the film, played by Marshall Colt, seems to be lampooning the actor. Hartman is fresh-faced, blond, and square-jawed — one of the younger generation on the Bulls football team. He’s referred to as a ‘Christian stud’, reading the good book before his games. Hartman is a figure of amusement and disdain to the rest of the hard-living, boozing athletes; his first appearance in the film is at a wild party, incongruously dressed in a tie and bringing his primly-dressed wife along as they discuss getting home in time to watch The Osmonds.

His clothing, hair, and bearing all heavily imply The Way We Were-era Robert Redford (the film came out in 1973 and was a box-office smash), but the film has no respect for him, really. He is an object of ridicule; we’re later told that Hartman has spoiled his snow-white image by having a drunken threesome behind his wife’s back; he also happens to be the guy who fumbles the all-important pass against Chicago, leaving him crying in the locker room. Hardly a romanticised image of the Good Guy jock of Redford dreams.

Rarely have I seen a sports movie which is so unsparing about its athletes’ weaknesses, injuries, and the slow descent toward obsolescence that any ageing player faces. You can practically feel Elliot wince in pain every time he moves, the broken-up joints and sour stench of old sweat in his clothes; he can’t even comfortably have sex with his girlfriend (Dayle Haddon) without something hurting. The nudity is matter-of-fact and unsexy, with Elliot’s best pal and fellow player Maxwell (Mac Davis) saying to Elliot: ‘you’re the only one I know with a body uglier than mine’.

The larger network of the team and its ownership is equally rotten. The Bulls promise to break a defensive opponent’s leg and follow through on it; their response to any guilt over it is: ‘fuck him’. There’s a team bully, giant redneck Jo Bob (Bo Svenson, also the baddie opposite Robert Redford in The Great Waldo Pepper), who sexually assaults women at a party. Maxwell, a walking incarnation of rape culture and not even one of the bad guys, says: ‘These girls know what happens at these parties. That’s why they come here.’ Elliot intervenes on a woman’s behalf and gets choked out by his teammate for his trouble.

Any sense of typical sports movie stuff – i.e. triumphant team spirit or friendship – is utterly curdled here; this is simply a disparate group of athletes on the downslide, breaking into petty fistfights. As far as the (never directly named) NFL is concerned, the rot is even worse. Ice-cold coach B.A. (G.D. Spradlin) is obsessed with computer technology and ‘synchronising’ the team – prophetic stuff for 1979. More pointedly, he’s looking for excuses to cut loyal but ageing players like Phil Elliot. There’s something particularly sad about the idea of a group of guys who are poorly equipped to do anything else with their lives and bodies – the case with most professional athletes, who single-mindedly focus on honing their talent in one direction – reaching the end of their usefulness. They are drugging, drinking, and smoking under a sword of Damocles, waiting to be fired or injured beyond help because they simply have nothing else to do.

As one incensed player, Shaddock (a memorably livid John Matuszak, a real NFL player), says: ‘You and B.A. and all the rest of you coaches are chickenshit cocksuckers. No feeling for the game at all, man. You'll win, but it'll just be numbers on a scoreboard. Numbers, that's all you care about. Fuck, man, that's not enough for me.’

It’s hardly surprising that the NFL did not look upon North Dallas Forty with affection, given its depiction of the sport as one of bottom-line oriented cruelty, drug use, and general lack of regard for its athletes. Apparently, several professional football-adjacent advisors and actors involved in the film were essentially thrown out on their ear by the organisation. As one ESPN piece has it: ‘Hall of Famer Tom Fears, who advised on the movie's football action, had a scouting contract with three NFL teams -- all were cancelled after the film opened.’

If American men were renegotiating what their manhood meant in this decade, the jock films of the 1970s point us in a few directions. There’s the ideal, and then the rejection of that ideal as something smarmy and false. North Dallas Forty is certainly the latter; few films of this era or any other feel so overwhelmingly downbeat and fatalistic about the realities of being a jock for a living. Boxing movies are accepted territory for the darkness and violence visited on athletes by corrupt governing bodies; very rarely does the rah-rah wholesomeness of American football get a similar treatment. It’s too middle-class, too historically white, too associated with the body politic of the American heartland itself. But no one in North Dallas Forty is having a good time - or if they are, it’s a temporary, substance-fuelled escape from the physical discomfort they’re facing.

The male athlete’s body and appearance is always political; always ideological. In art and sculpture as well as politics, it has been a source of obsession. Connected to virility and even virtuousness since antiquity, it’s not difficult for this thinking to tip into something like the physical culture obsession of eugenics, which handily connected strength, athleticism, and physical ability to political power, and therefore any physical disability to weakness. So, to put it mildly, the deification of the athlete can be dangerous. What we see in the active breaking-down of the jock body in films like North Dallas Forty is a subversion of the entire glorified symbol of the Redford jock and his ilk. The film sympathises with inevitable wear and tear, depicting a body – and a man – who is broken down to the point of surrender.

It’s crucial that Phil Elliot ultimately steps away from the sport, and from business of trying to prove his macho credentials, his physical superiority, or his ability to win. He sees it as the fools’ errand it is. The film was about ‘the institution of football,’ Nick Nolte said in an interview at the time. ‘Or about any institution.’ That institution might be American manhood at a crossroads, or it might be the viciously capitalist influx of corporate money and tech into professional sport. But very few jock movies spit in the eye of those institutions with such doomed defiance.

~~~~~

Thank you for subscribing to the newsletter, and taking an interest in my essay series on men and masculinity at the movies, Dudes Rock!. Join me throughout August for more explorations of the nooks & crannies of masculine movie culture and its discontents.

Fascinating piece (and the audio version is a great addition) about a movie I was completely unaware of. It did bring to mind Number One (with Charlton Heston) - another pretty bleak look at a jock reaching the end of the line?

As an outsider, US football culture (NFL, but maybe even more so college football) does simultaneously intrigue, baffle and sometimes appal me. So much going on that just isn't questioned (as is certainly the case with, say, football in the UK).