In Sicily, Women are More Dangerous than Shotguns

On 'Donne di Mafia' and Organised Crime in Italy

‘When I first interviewed a criminal...we talked about The Godfather.’

Dr. Felia Allum knows a bit more about the Italian mafia than most of us. She’s a senior lecturer in Italian and Politics, with a specialism in women and organised crime, and in her role as an academic she has extensively interviewed ex-criminals, law enforcement, and anti-mafia prosecutors for years, which makes her a pretty incredible authority on the topic -- and is also how she ended up screening a mini film-festival all about it. This month, I’ve dedicated my substack to a collaboration with Cinema Italia UK’s ‘Donne di Mafia’ festival, which earlier this month screened six female-centric films about women with mob ties, programmed by Dr. Allum. What I learned from our conversation - and from watching these movies - was that women’s roles within this world are so much more complicated than I had ever originally assumed, and that women can so often be, as Allum has it, ‘both victim and perpetrator’.

If asked to think up some choice images from films about the mafia, I think of ‘men of honour’ in mid-century coats and hats; the arid plains of rural Sicily, and a dark-haired girl named Apollonia in peasant clothes; women who recede to the corners and watch doors shut in their faces as their men plot vendettas and power-grabs. Mostly, there’s an image of women as wives and daughters, passive, leeching onto male power. Even in Italian cinema, a handful of auteurs dominate international film festivals with their depictions of the mob, Matteo Garrone (Gomorrah, 2008) and Marco Bellochio (The Traitor, 2019) chief among them. The genre movies and poliziotteschi of the 60s and 70s offered several entries, among them Damiano Damiani’s Day of the Owl (1968) and Pasquale Squitieri’s Gang War in Naples (1972), but Eurocrime is a subject very much for another day. Dr. Allum’s programming for ‘Donne di Mafia’ is not so interested in the carnage of the past, and even less in the thrills of genre cinema, instead proffering a selection of younger filmmakers who are lesser-known outside of Italy. As a result, the oldest of the films by a decade is from 1998; the majority land in the 2010s.

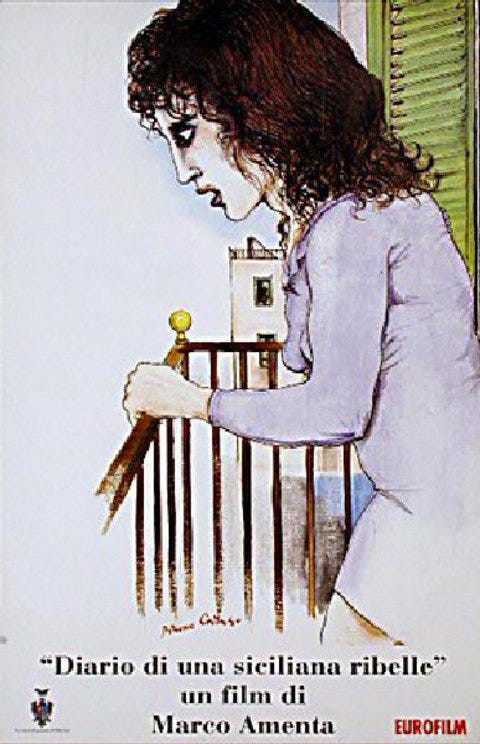

The films selected for ‘Donne di Mafia’ posit a real antithesis to what has come before; they depict mafia bosses as sex traffickers and rapists (La Terra dei Santi). Or sainted Sicilian mothers threatening their children with death if they turn state witness (Una diario di siciliana ribelle). Or young Neapolitan women tortured and murdered for information they might not even have (Gelsomina Verde). These are not nostalgic images of a criminal hierarchy where respect, family and honour mean something; they are much closer to reality, and often discomfiting as a result.

I think many of us who have watched and loved The Godfather, Goodfellas, The Sopranos, and all of those English-language, Italian-American screen iterations of the mafia, have the tendency to lose sight of what it actually looks like in Italy, and what a corrupting, corrosive force it remains in Italian political and social life. These are powerful secret networks made up of regional groups - in Calabria, the ‘Ndrangheta, in Naples, the Camorra, and in Sicily, the Cosa Nostra - and then further divided into families and clans, many of whom have erupted into their own internecine wars. When English language films do extend to the old country, their depictions tend to be romanticised.

They are images, as Dr. Allum points out, of ‘traditional Italy as it was. There’s this image that the Cosa Nostra is a product of a backward society, when it’s actually a highly adaptive, innovative criminal organisation.’ In The Sopranos, for example, there’s an episode (Commendatori, S2) where Tony and company visit their Italian cohort, and it leads to a series of culture-shock laughs at their expense, proving to these New Jersey natives that they are truly far from home. The more restrictive and reactionary Italian hierarchy is an eye-opener to them, but it is still, much like other American depictions of the mafia, hamstrung by romantic mythology, forever imagining the Cosa Nostra as set in a pastoral past rather than the transnational, thoroughly modern billion-dollar organisation that they are.

And yet even the mafiosi look to the movies to find images of themselves, even if they’re not entirely accurate. ‘Were you influenced by the film, or was the film influenced by you?’ Dr. Allum asked her interview subject who professed his love for The Godfather. He’d be far from the last gangster to copy-cat the style or attitude of screen hoodlums; ask London spivs in the 1940s where they got their dress sense from, and they’d inevitably tell you it was George Raft.

All of this is to say that movies are, for good or ill, powerful tokens, and that even for the keen-eyed among us, it can be difficult to puncture their mythology. When it comes to women of the mafia in real life, they run the gamut from prosecutors and magistrates to victims to domineering wives. In the words of Dr. Allum, ‘I’ve come across various cases where the men went out and did the shooting, but the women organised the whole thing, and were the ones who said, “if you don’t go out and shoot him, don’t come home”’. Even a cursory google search shows a long list of gunwomen, financial advisers, and racketeers for the mob; in spite of not being officially allowed to join the ranks, they are everywhere, at every level. In organisations so obsessed with blood ties, the fact that the ‘crime’ family and the actual one overlap through mothers and wives should not be too surprising.

‘In Sicily, women are more dangerous than shotguns.’

Or so says The Godfather. It’s an allusion to the fierce protectiveness of mafia fathers and husbands, which made these women tantalisingly untouchable to Michael Corleone. But there’s another, more openly subversive meaning it may have developed over the intervening years, as former mafia women break Omertà to come forward and report on gang activity to the authorities. It’s the sort of rebellion that these ‘men of honour’ could hardly see coming, such was their confidence in male supremacy. It’s not just in Sicily, of course, but across Italy, and the increased role of women as state witnesses has been the source of great surprise.

Because women’s roles in the mafia have been so profoundly underestimated, often both by the authorities and by the men who run their criminal organisations, it has proven a catalyst for the same women to gain power (legal restrictions on prison visits, for example, mean that wives and close female relatives are some of the only people to be able to communicate with imprisoned bosses and convey their orders). Conversely, it often means women can provide a great deal of information to anti-mafia prosecutors should they turn state witness. In Marco Amanta’s Diario di una siciliana ribelle, or One Girl Against the Mafia (1998), a remarkable documentary sharing the diaries of mob boss daughter Rita Atria and her decision at only seventeen to speak to the authorities, the inherent dangers are obvious. As Atria herself put it: in Palermo, where she grew up, you would sooner kill your best friend than talk to the police. Anywhere else, that might be hyperbole. The knock-on effects of breaking that silence can’t be understated, and since the Italian version of the witness protection programme has only existed since 1991, there are far too many cases of information leaking and informants being killed. Atria did not survive, nor did she expect to, but she did take down dozens of high-ranking mafiosi, shocking authorities with her deep insider knowledge and even uncovering the gang-ordered killing of a politician.

In the moving 2015 film from Fernando Muraca, La Terra dei Santi, young and ambitious magistrate Vittoria (Valeria Solarino) moves to Calabria to weed out members of the ‘Ndrangheta. But the story is told as much from an insiders’ perspective as an outsiders’; it also shows the plight of young mob wife Assunta (Daniela Marra) who, after her husband was killed in prison, is forced to marry his brutish brother and watch helplessly as her teenage son is recruited into the ranks of an army which is sure to see him dead before twenty. The film has some soapy, too-convenient narrative dimensions, and the production values are crisp in a vaguely televisual way, but the acting and writing is utterly compelling. Vittoria’s fight for the greater good can’t help but to inflict more day-to-day misery on the beleaguered Assunta, particularly when Vittoria threatens to put the ‘Ndrangheta mother’s children into custody.

The choices faced in these situations are all too real, as reporter Alex Perry writes in his book The Good Mothers: ‘The severity of the misogyny prompted some prosecutors to compare the ’Ndrangheta with Islamic militants. Like ISIS or Boko Haram, ’Ndranghetisti routinely terrorized their women.’ In contrast to the honourable image of mafia men, women like Assunta may be subjected to forced marriage, sexual violence, constant chaperoning, and the threat of being kept from their children. They maintain any control only through keeping their sons and husbands out of prison and alive, which is no mean feat in their profession. Her character’s damning conclusion is summed up in a Fitzgerald-esque line about the gender of her unborn child. Asked by the magistrate if it’s another soldier for ‘their army’, Assunta pauses and says: ‘If he’s lucky. Otherwise, it will be a girl.’

Yet there’s a third role in La Terra dei Santi which offers another perspective: that of bosses’ wife Caterina (Lorenza Indovina), a coolly unbothered, well-kept woman who acts as Assunta’s confidante but gives the uneasy sense that she can pull rank on the younger woman at a moment’s notice. In one bone-chilling moment, she views a murder scene with a vague, unconscious half-smile; she is so inured to violence that she is merely relieved it’s no one she’s related to. In her expression of a rotted soul, her total identification with masculine power and violence is also a stark reminder that there is no clean delineation between emancipation and victimhood.

I’ve never been one to argue that cinema should maintain complete fidelity to reality, or that accurate representation should be king. My favourite movies are transportive, mythological, ambiguous, even fantastical - and god knows the last thing we need now is more literal-minded, didactic art. But the disparity between reality and fiction, as quite troublingly laid bare by ‘Donne di Mafia’, is enough to give anyone pause. It’s a much-needed corrective to what outsiders think we understand about this world and its complexities. It reminds us that The Godfather’s old quote about dangerous women is truer than we all probably thought, but in ways many of us had never begun to imagine.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Later this month, I’ll delve deeper into some of the other films in the ‘Donne di Mafia’ lineup, including via a video introduction and some other extras!

If you would like to become a friend of Cinema Italia UK, you can do that here.

Thank you for a really fascinating piece - it taught me as much about society as it did about film. I have thought before about the feedback loop of glamour that comes from the characters (particularly) in The Sopranos constantly discussing The Godfather. Michael and Sonny were glamorous, Tony and Paulie get some of that reflected glamourous and magnify it by knowing and discussing the details of Moe Greene's killing. And so it goes.

And these movies look fascinating, I feel like a counterbalance to the romanticised view of organised crime (not that I don't love those movies!) is overdue.