Steeped in the Air of Death and Sperm

Promiscuity, Film Noir, and Luchino Visconti's Ossessione

When, in 1943, Italian director Luchino Visconti released his debut feature Ossessione, fellow filmmaker and critic Giuseppe di Santis rather memorably described it as having an atmosphere ‘steeped in the air of death and sperm’. Benito Mussolini walked out of a screening in disgust, ordering all prints of the film destroyed; in one town, Catholic bishops performed an exorcism of a cinema it was shown in. Released as it was into a fascist Italy obsessed by family values and sabre-rattling machismo, and concerning as it did matters of adultery, murder, unwed pregnancy, and homosexuality, it caused a stir that’s difficult to imagine today. In other words, it’s the sort of film you’re predisposed to like. Because of Mussolini’s ban, it became nigh-on-impossible to see at the time, and was equally unavailable in the United States because of its copyright breaches -- though today, it’s available to stream on Amazon Prime, so, hooray for that, I guess.

If you’ve seen The Postman Always Rings Twice (1946), a cornerstone of American film noir starring John Garfield and Lana Turner, the plot of Ossessione should be familiar - though, in fact, the Italian version predated the American adaptation of James M. Cain’s source novel by three years.

The story centres around a handsome, impoverished young drifter, Gino (Massimo Girotti). Gino wanders into a bar run by old man Bragana, husband to the much younger Giovanna (Clara Calamai). Gino and Giovanna begin an affair, eventually plotting to murder her husband and then making an attempt to live out their guilt-stained lives in the aftermath.

Visconti, a gay aristocrat born into unimaginable luxury who developed into a Marxist at a relatively young age, had an approach befitting his status: paradoxical. He would distinguish himself as a filmmaker simultaneously blessed with the ability for painterly, decadent production design, salt-of-the-earth realism, and rigorous formalism, and his work would grow more baroque (see: The Leopard) as time rolled on and budgets grew. But Ossessione, his first feature, was necessarily made on a shoestring, released the same year as Italy’s crushing defeat and occupation by Allied forces. Visconti - not long sprung from imprisonment after an arrest for aiding the Resistance - portrays the misery, solitude, lust and guilt of his protagonists, fully flouting the smarmy false optimism and cheer of Mussolini's 'white telephone' movie industry. The government remained deeply invested in cinema for purposes of boosting Italian morale, and tended to produce escapist fare with nationalistic, traditionalist tendencies. Although many directors (Roberto Rossellini, to name one) got their start at Cinecitta under Mussolini, the deeply taboo Ossessione proved to be too outrageously against the grain to ignore.

Ossessione is marked by many of the tendencies of neo-realism. It naturalistically captures ordinary streets, shops, and bars in the Northern Italian region in and around Ferrara; it takes an interest in the social dynamic between rich and poor, between the materialistic and the free-spirited; and it has an earthy, frank characterisation. Yet, as Visconti’s later films would prove in high operatic style, absolute realism was not his goal. His actors are a good deal more glamorous than the supposed tenets of neo-realism would call for; both Girotti and Calamai, as the ill-fated lovers, were established Italian movie stars, with no small amount of personal beauty.

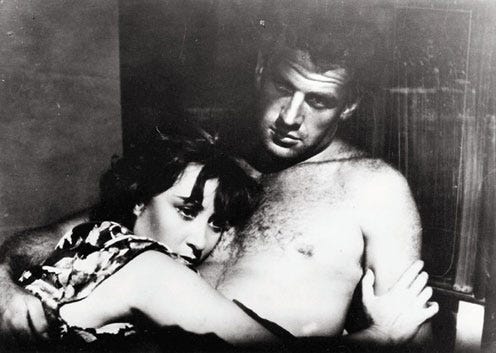

Girotti anticipates the testosterone-drenched magnetism of a young Brando, with his broad shoulders and torn white vest, and Visconti's many lingering shots on him serve as an interesting counterpoint to the typical erotic woman of film noir. Visconti upends those gender relations by casting such an admiring eye on his male lead, wedding the camera to Giovanna’s lusty perspective and frequently foregrounding Girotti in the frame. The ex-champion swimmer was also the focus of Visconti’s attentions in real life, but that’s a story for another time.

Clara Calamai, a popular Italian star who was known for her daring (she appeared briefly topless in a film the year before, though is best known today for her role as Marta in Dario Argento’s Profondo Rosso, from 1975), was stripped back in her appearance, with Visconti scrubbing her of any sophisticated makeup or hairstyles. The aim was for her to give the impression of a less-than-perfectly-prim housewife, with an air of wilted, hungry sensuality in search of an outlet. This provides an interesting contrast against Lana Turner’s unforgettable embodiment of Cora, an immaculately-dressed and noticeably lipstick-touting version of the same character, carefully baiting her prey in the form of John Garfield; her affection for him seems minimal, by comparison to Giovanna’s fixation on Gino.

As both a committed Communist and a nostalgic aristocrat, Visconti knew what it was to straddle two worlds, and Gino and Giovanna do too; they have flouted all traditional morality, but remain shackled to their worldly goods, attempting to take over and run a business in a respectable manner in the wake of their homicide plot. The carefully constructed, almost alien beauty of Visconti’s wide shots capture the whitewashed, flat landscapes of Northern Italy, dotted with black-ensconced, windswept figures moving like ants across the vast space. Gino and Giovanna are two such insects, occupying their own remote world and unmoored from the social structure.

The kinds of tensions and secrets they keep cannot survive in the light of day, and tragedy arises not out of any misplaced desire for moralism, but a sense of inexorable guilt and doom. It’s a choice which also redirects some of the blame which is typically cast on the seductive female; Giovanna is torn between bourgeois comfort and love, but she isn’t the grasping, conniving femme fatale we’ve come to associate with the genre, and in some respects, she’s closer to James M. Cain’s ‘hellcat’ of the novel than Turner’s version, who is a much more coolly calculated figure.

Visconti’s subversive inclinations feel all the more apparent when compared to Tay Garnett’s 1946 adaptation, backed by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. There, it took over a decade for the story to reach the screen because of the censors, who openly objected to the book being adapted at all. The Postman Always Rings Twice is audacious for its time, but it turns murder into a convenient accident and excises any real sexuality; ultimately, it’s still hidebound by the Production Code.

Turner is perhaps at career-best here, but she is still portraying a relatively paint-by-numbers dame, camera lustily tilting up her bare legs as she uses her feminine wiles to ensnare John Garfield, the perennial rumpled everyman. There’s lots to admire in the film, to be sure: star power and sensuality not least among them. But there’s little denying the schematic nature of Tay Garnett’s version, with its traditional noir dichotomy between female mendacity and male righteousness. In the end, there’s something too MGM, too clean, about The Postman Always Rings Twice for me; there’s just less dirt under the fingernails of the American version of the story. This may be because I actually saw Ossessione first; the brooding power of its imagery never did leave me, nor did the unabashed power of its lust.

Giovanna is far less knowingly manipulative than her American counterpart, Cora. As Cinéaste writer Martha P. Nochimson puts it, ‘She responds instinctively to Gino’s sensuality; he is never the same means to freedom and wealth that set into motion the cold calculation of […] Cora Smith.’ Nochimson goes on to note the lack of careful planning on the lovers’ part; for them, murder is the result of an uncontrollable spiral of events – Giovanna is led by blind desire, not greed.

There is something genuinely subversive about the idea of Giovanna being led by half-mad lust, the domain of the masculine. That it then causes a break up of the precious family unit of a middle-class Italian household, to run away with a vagabond and become pregnant with his child, is even more remarkable. Women’s lives were tightly circumscribed by religion and state in the Mussolini era, with a particular focus on, essentially, being an obedient breeder of more loyal Italian sons. (After 1927, education about birth control was explicitly banned in Italy, and at the height of Mussolini’s regime, medals were given to women who produced large families.) But Ossessione refuses to venerate the maternal, or allow it to ennoble this character; Giovanna is the same as she ever was, only pregnant. Then, to really make the fascists mad, she dies.

Ossessione goes further again, too. The film not only swaps out the role of the erotic film noir woman for a man, but another character – a male friend, Spagnolo – appears as an indirect rival for Gino’s affections. Though it is never explicit, Spagnolo offers Gino an escape into a gay lifestyle, and the scenes between the two men allow for male friendship and attraction in a manner which parallels the relationship between Gino and Giovanna. The character of Spagnolo, a Visconti invention not appearing in the novel, disappears entirely from The Postman Always Rings Twice.

Visconti’s first and only foray into ‘neo-realist noir’, viewed today, is an unwieldy, moody combination of class warfare, postwar fatalism, and sexual murkiness. But its nuances, its sensuality, and its reversal of traditional roles allow it to critique the values of Mussolini’s regime – and to provide a fascinating counterpoint to Hollywood’s treatment of the same source material. Visconti's technical virtuosity and flair for the tragic infuses the tale with fresh interest and a thoroughly Italian approach to postwar American attitudes, and its languid pace teases out the complexities of Cain’s story, bringing gender dynamics to the fore in unusual ways.

In Ossessione, no one is innocent; Gino and Giovanna are in many ways equally culpable for their crimes. In a strange way, that equal culpability - that mutual sexual abandon - is its own wicked form of equality.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

If you enjoyed this edition of Sisters Under the Mink and you haven’t yet subscribed, you can do that below. This month will be the last with all material totally free, and there’s a whole bundle of stuff coming this March!

Finally, a question for anyone who might like to discuss below: what are your favourite adaptations of famous crime novels?