On the 15th July, 1955, in Naples, eighteen-year-old Assunta Maresca pulled a Smith & Wesson out of her handbag and shot her husband’s killer dead in broad daylight. She was six months pregnant at the time. A beauty pageant winner and daughter of a Camorra crime boss, Maresca had been widowed by a fellow mafioso who’d actually been a guest at her wedding. Given their involvement in organised crime, she was certain that police would take no interest in bringing her husband’s killer to justice. Young, beautiful, and defiant, it was no surprise that Maresca caught the attention of the media.

When, in 1959, before a veritable whirlwind of reporters and crowds (it was the first time the court allowed microphones in, so crowds could hear what was being said) she was sentenced to eighteen years in prison and scoffed to the gathered crowd: ‘I’d do it again.’ The courtroom was said to have burst into cheers.

Even then, she was already known as ‘Pupetta’ Maresca, or ‘Little Doll’, for her petite beauty. She would also later be nicknamed ‘Lady Camorra’ or ‘vedova nera’ (‘black widow’). Such was her effect on the public imagination, that her death - last year, aged 86 - was front page news in Italy. She was kept consistently in the headlines over the decades by various connections to homicides, arrests, and - you guessed it - films and TV shows about her. There have been at least, by my count, four of these that were directly inspired by her. The most recent - a four-part miniseries for Italian television entitled Pupetta - The Courage and the Passion, aired in 2013.

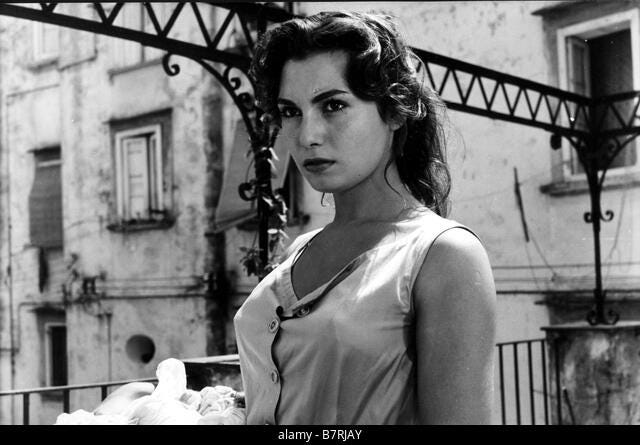

Somewhat remarkably, that life/art imitation began over half a century ago, when Italian neorealist filmmaker Franceso Rosi began production on La sfida (The Challenge) before the teen Maresca had even been sentenced for her crimes. This film, released in 1958, remains the most respectable of the cinematic output concerning Maresca, where her screen proxy is played by the beautiful Rosanna Schiaffino.

Francesco Rosi was heavily influenced and in fact mentored by Luchino Visconti, from whom he borrowed many working methods and tendencies. You can see his love of Visconti in the granular black and white street scenes of La sfida, which sometimes resembles Visconti’s earlier work (La terra trema and Ossessione in particular), as well as in his taste for a dash of melodrama in spite of an otherwise naturalist style. Yet as visually strong as the film is, it essentially relegates Maresca to a supporting character in her own story. In the film, she gets less dialogue than she gets sultry stares, seducing her husband-to-be Vito (José Suárez) as she hangs laundry in the narrow block they live in. For Rosi, it is Vito who is an interesting representation of Neapolitan street life, of the collusion between business and organised crime, and of the tragedy of life lost so young. At one point, Assunta says something eye-rollingly jejune like ‘I’d rather not have a penny but be able to live with my husband’, and Rosi leaves her to weep over Vito’s body in the closing scenes: we don’t even get her revenge.

Meanwhile, in real life, Maresca served thirteen years in prison for that revenge, giving birth to her son there and soon, by merit of having assumed her husband’s authority, became something like the boss of the joint. Other inmates came to her with small gifts and requests, which she did her best to help with. When she emerged, her teenage son was already a local hoodlum, and she had no intention of living quietly, either. She remarried another camorrista, a charismatic cocaine and arms smuggler called Umberto Ammaturo, and went on to have twins with him.

In 1967, Maresca appeared in a film about her own life, or loosely based on it, entitled Delitto a Posillipo: Londra chiama Napoli (Crime in Posillipo: London calls Naples). She even sang in it, somewhat bizarrely - how many other movies can boast a musical number featuring a convicted murderess? You can see Maresca’s much-vaunted prettiness here, with her shiny black hair and almond-shaped eyes heavily lined in sixties style. But to star in a life story at this point was a premature choice: there was too much insanity yet to happen to commit her story to celluloid.

In the early 1970s, her oldest son, the one she was carrying when she committed her infamous revenge killing, disappeared altogether. She long suspected her own husband, Umberto Ammaturo, of killing the 18-year-old, saying that if she’d had the appropriate evidence, she ‘would have killed a man for the second time’ in her life. But she didn’t act on her suspicion: it wasn’t advantageous to do so when Ammaturo provided a lavish lifestyle for his wife and their two young children. The pair would later be accused of ordering another murder, for which Maresca would serve four years before being released on lack of evidence. She maintained her innocence, which I frankly hope is true, because they found the guy decapitated, with his severed head in between his legs. Given that Maresca was understood to be one of the leaders of the Camorra gang known as Nuova Famiglia, I can’t imagine she was clueless about any of this.

Two more television shows followed, the first in 1982, entitled Il Caso Pupetta Maresca, directed by Riccardo Tortora and Marisa Malfatti and starring the granddaughter of Il Duce - Alessandra Mussolini - in the lead role. Mar1esca, calling the casting decision an ‘affront’ to her honour, took the makers of the docu-drama to court, effectively preventing it from being shown on Italian television until 1994. (There is woefully little information I could dig up on this iteration of her life story, especially with my lack of Italian. If any Italian-speakers do know more about it though, I would love to hear from you.)*

[**NOTE: Here’s an archive piece on the show, thank you diligent readers!]

Finally in 2013, Pupetta - The Courage and the Passion, which I can only describe as a glamorous hagiography, came along. The miniseries presents Maresca as a girlbossified victim who empowers herself in spite of abuse on all sides, and was released on Italy’s Channel 5 to mixed reviews. Many anti-mafia campaigners found the whole concept of the show distasteful, and I would tend to agree. Manuela Arcuri, the lead actress, got into some hot water last year in an Instagram tribute to Maresca after her death, and her endless praise for Pupetta does go some way to suggesting the tone in which this project was undertaken.

Maresca, seemingly placated by her depiction in the show, remarked that she saw her own temperament in the performance of lead actress Arcuri. Still. She was a little annoyed they’d changed her name.

~~~~~

When do you relinquish the right to tell your own story? Or at least get some say in how a film about your life is made? The answer, for the most part, is that if you’re a public figure, you’re legally fair game. Whether that’s a straightforward biopic or a loose fictionalisation, if the story or events contain publicly-known facts, you’re probably safe. Of course, most filmmakers do request permission or rights from the person, if living, in order to circumvent any issues (read: lawsuits) later on. But legal and ethical are two very different things, as this newsletter’s existence has probably borne out.

We’ve seen it recently with Hulu / Disney+ show Mike, the miniseries about Mike Tyson which critically addresses his rape conviction, and was made without the boxer’s input or endorsement. Tyson took to social media to complain about it. Pamela Anderson also talked about the distress she felt at not having been consulted for the miniseries Pam & Tommy, which recalled sensitive and often traumatising parts of her life in detail, and with plenty of artistic licence. (Anderson has hit back not with a lawsuit, but with a promise to tell her own story in a film for Netflix: a savvy move, far more likely to sway public opinion than litigation or social media bitching.)

Does Tyson, as a convicted felon, relinquish his right because he has no moral high ground to take, or because the perception of his trustworthiness is forever skewed? I would say he still has some grounds to complain, but his involvement is also compromising in a very specific way: it would not immediately make for smart - or ethical - filmmaking if the creators were beholden to his oversight or version of events. And what about Pamela, whose only crime (read: not a crime at all) was to be the ur-object of desire for a generation? Surely in this case, her involvement could be corrective, helping to shift the biographical and cultural narrative of what happened to her in those years? It says something, I think, about my contrasting response to their pleas. A male victimiser and a female victim, in turn: of course I want to hear from one and not the other. But where on the ethical grey scale does that put depicting the life of Assunta Maresca, a woman who almost certainly was both victim and victimiser in her time on this planet?

Passing simple judgement on her seems like a fool’s errand given how much her life was defined by traumatic circumstances, unimaginable to most of us today: pregnant and widowed before out of her teens, surrounded by violence (even her brothers beat her, as a teen, when she caught a man’s roving eye) imprisoned, separated from an infant at birth. Then she lost that boy, also not out of his teens, to a violent murder most likely committed by her second husband.

And yet, the real Maresca was a complicated and amoral woman. She once said in an interview: ‘I had killed for love, that is, to avenge my man, and not to be killed myself. Not only me, but also the child I was carrying. That is, I shot in self-defence.’ That may be at least partly true, but as author Claire Longrigg points out in her landmark 1998 book Mafia Women (in which she extensively interviewed Maresca), there were more beneficial motives at work. By murdering her husband’s killer, Maresca was essentially ensuring her status as the widow of an important boss, assuming the power as a ‘woman of honour’ to be respected and feared. There were strategic reasons for her decision in the vein of a true mafioso, rather than a crime of passion or of self-defence. If she were simply a hot-tempered killer, what do we make of her choice not to attack her husband for his suspected crime against her own child?

Surely if there’s anything we’ve learned this week post-Blonde debacle, it’s that if you were a famous woman of the past century, and a man comes calling to tell your story (or kind-of tell your story) for the screen, you had better beware. It makes me think: hell, why shouldn’t Maresca have tried to control her own narrative, even if she was awful? Newspapers wrote that she was vulgar; anti-mafia campaigners lobbied against her glamorisation onscreen (and perhaps they were right), but she remained heavily involved and invested in how she was depicted over the many decades of her life.

Maresca was a woman who was canny about publicity from the off, else she wouldn’t have starred in a film about her own life. She was always happy to give a melodramatic line to a reporter, or wear a low-cut blouse to a press conference where she publicly threatened a rival gang member of the Camorra. As Longrigg observed, it kept her in focus while her brothers, husband, and other men of the family business went about their activities unimpeded.

And so it becomes increasingly clear that even the most humane moments of Maresca’s biography are coloured by a certain amount of shrewdness. Was she truly so convinced that Mussolini’s granddaughter playing her was an affront to her honour, or was there something else about the depiction that she didn’t approve of?

And even still, in light of the ‘kill or be killed’ flavour of the stories we tend to see about famous women as of late - filmmakers from Pablo Larrain to Andrew Dominik seem to traffic in them, for better or worse - I don’t really mind that amorality. If it is kill or be killed, at least Maresca chose the former and survived to the ripe old age of 86.

In the end, the old woman died in the same village she was born in, the better part of a century later. Given her tumultuous life, I’m sure she did not emerge unscathed. But at least she survived to tell the story - whatever version that was - herself. If you’re a controversial woman, god knows that’s probably the best option.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Thank you so much for reading Sisters Under the Mink. If you enjoyed this and would like to upgrade to a paid membership, the newsletter relaunches this month with audio/visual goodies, interviews, and extras galore for paid subs! If not, I’d be much obliged if you’d like to share it with your pals on social media, etc.